One of the more contentious, yet consequential, political disputes currently dominating the national conversation centers around when and how to re-open the economy. With conservatives largely wanting a swift return to normal economic life and progressives advocating for a more cautious approach, this question has become entangled with political talking points and dogmatic commitments.

At the center of the debate is how to best balance health risks with economic activity. Even without political partisanship, striking the right balance is difficult. Open too quickly, and COVID-19 will come surging back, sickening and killing countless people in the process. Open too slowly, and the economy will continue to deteriorate, throwing millions of people further into financial hardship and causing even more businesses to permanently close.

Neither scenario is ideal, but fortunately both can be avoided. Instead of having a conversation driven by politics, an evidence-based approach relying on data is possible. For instance, Facteus, a company that provides consumer spending data to hedge funds, recently analyzed troves of synthetic data to determine how to best balance health risks with economic benefits.

To understand how data can guide the reopening process, PaymentsJournal Editor-in-Chief Ryan McEndarfer sat down with Randy Koch, CEO of Facteus. During the conversation, Koch and McEndarfer unpacked Facteus’ findings and discussed what synthetic data is and how it can be brought to bear on topics far beyond just reopening.

Using data rather than opinion

Since the current dialogue around reopening is often disconnected from data and evidence, it has been largely ineffective.

“It’s pretty clear that we are miserably failing at answering this question on how we [should] safely reopen the economy,” Koch said. Instead of using guesswork or political dogma, Koch explained how Facteus’ “premise is that data needs to answer this question.”

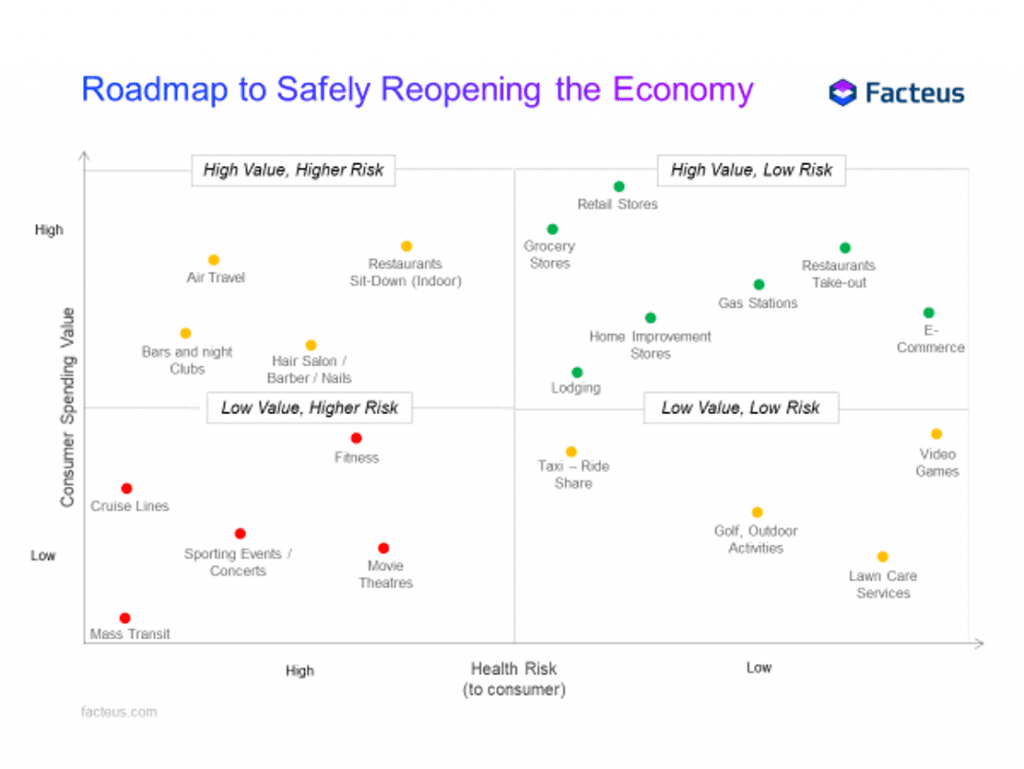

Specifically, Facteus used data to map how the health of consumers interacted with the economic impact of certain businesses reopening. Such an approach allows policy makers to know which businesses openings are low risk but high reward, which are high risk but not economically rewarding, and all the other permutations in between.

In other words, Facteus’ data-driven approach “shows a clear mechanism on how we safely reopen the economy [and one] that is based on data and not opinions and not guesswork,” said Koch.

Quantifying health risk and economic impact

Facteus’ findings, shown below, offer a compelling look at how to safely reopen. The graph shows consumer spending value (on the x-axis) plotted against the health risk to consumers (on the y-axis) for a variety of different businesses.

Based on the findings, it is evident that some business openings offer great economic benefits without serious health risks. For example, allowing restaurant take-out results in high consumer spending but with a low risk to consumer health. In contrast, cruise lines offer less economic benefits but more health risk.

“Once you simply map [health risk and consumer spending value] together, it gives a very clear idea on what you should open now, what you should open later,” explained Koch.

However, he was quick to note that opening decisions can and should vary by state. What Facteus’ graph offers is a framework to have data-driven discussions. “We want [states] to use this data, customize it for their local jurisdiction, and have a clear way to reopen the economy, or at least a framework to have these discussions,” said Koch.

The data behind Facteus’ “Roadmap to Safely Reopening the Economy”

In order to determine the consumer spending value, Facteus analyzed data from over 1,000 banking institutions. All told, the data encompass nearly 50 million card transactions per day, broken down by different industries. This allows for the economic impact of restaurants, for example, to be compared with the impact of opening nightclubs.

Notably, Facteus anonymized and aggregated all the financial data to ensure nobody’s personally identifiable information (PII) could be compromised, creating what is known as synthetic data.

To determine the health risk of each business, Facteus relied on 20 different sources from the health industry and “mapped those sources together on which of these categories is highest risk versus lowest risk,” explained Koch. For example, since most health experts agree that live sporting events—where tens of thousands of people pack into a space together—are high risk, Facteus rated that business type as being high risk.

Once the economic impact is plotted against the health risk, it becomes easier to determine which businesses should open and which should wait.

More on synthetic data

Facteus’ approach was made possible by using synthetic data, a term that many readers may not be familiar with. In order to understand what it is, one must first understand what normal data is and why companies, especially financial companies, can be very hesitant to use it.

When a person makes a transaction, a lot of information is generated, including the person’s name, card number, transaction amount, location, time, and many other data points. All of this is just normal data. Since the data contain sensitive information, regulations exist governing how financial companies can use and share the data. Because of this, many financial institutions have been very cautious in leveraging data.

Synthetic data sidesteps these security and regulatory concerns. It takes normal data sets and anonymizes and aggregates them so that no personal information is being used, but relevant statistical patterns remain intact. Therefore, “synthetic data is a way that makes sharing data absolutely secure, safe, and regulatory compliant,” said Koch.

He offered an example to help illustrate his point. Consider someone making a purchase at Starbucks for $2.12 at 7:02 in the morning. To convert that into synthetic data, the time may become 7:20 while the transaction amount may become $2.20. When such a process is applied to millions of transactions, the key patterns remain but information that could reveal the actual identity of those making the transactions is stripped away.

Benefits of synthetic data

Since the data becomes truly anonymized, companies can safely use and share it without worrying about violating regulations or compromising consumers’ personal information.

Sharing data offers a range of benefits. More data leads to better decision making, both in industry and public policy. From the industry perspective, companies can use synthetic data to figure out the best location to open a new branch or store based on spending and traffic patterns.

On the public policy side, more data means more informed policies. For example, The Federal Reserve collaborated with Facteus to leverage synthetic data to better understand how the stimulus package impacted consumer spending. And without synthetic data, Facteus would not have been able to analyze mountains of consumer data to make its roadmap to reopening. But since the data was anonymized, banks were willing and able to share it, and Facteus was able to present its findings to the public.

Beyond making data sharing easier, synthetic data can also lead to monetization opportunities, a fact that Koch had previously explored in-depth during a PaymentsJournal podcast. “You can create new revenue streams safely from your data exhaust,” said Koch. Many other industries, especially big tech, are already monetizing consumer data, and synthetic data empowers financial companies to do so too.