In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the U.S. government is contemplating sending Americans $1,000 to help ease the financial burden they are facing because of this crisis. I won’t get into the political arguments on either side of this decision. What I would like to talk about is what happens when the money arrives.

Chances are that if this money is disbursed, it will be in the form of a paper check mailed to people’s home. The IRS and other agencies do have the capability to electronically transfer funds, but those all require consumers to register and provide information that gives the government email addresses, account information, and an authentication method.

The federal government certainly does not have all of this information for all its citizens, and in the 2008 crisis some people received their check this way. That leaves the paper check for many Americans.

What happens when the letter carrier delivers the check to millions of doorsteps, particularly in the era of self-imposed (or not self-imposed) shelter in place protocols and social distancing?

What came to mind is how people will get the funds from that paper check into their financial institution’s account. There are three primary methods for depositing checks in the U.S. – at a branch, at an ATM, and through remote capture via a mobile banking app.

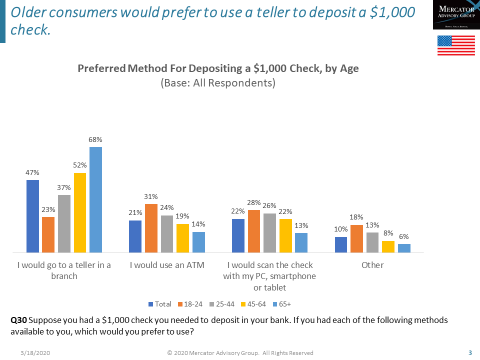

Our most recent PaymentsInsights survey asked American adults about how they would deposit a $1,000 check (note: this survey was conducted in November, pre-COVID-19). Our data show that there are meaningful differences in the methods people choose in making a $1,000 check deposit. The biggest differences we see are related to age and annual household income.

As the chart below shows, 7 in 10 (68%) of consumers 65 years of age or older would prefer to use a teller to deposit a $1,000 check. Some of these people will be able to switch to another method of depositing this check, but others will not. Many older Americans have eschewed technological options for banking in favor of the method they know the best – and that does not bode well for them getting the money into their bank.

Similar results can be found when we compare the survey question among income levels. Preference to visit to a physical bank with a teller interaction is highest among those who are in the lower income brackets.

While these data points were collected before COVID-19, it points to a need that may develop among older and lower income adults on how they will get the government money into their bank accounts. Yes, many bank branches remain open and ATMs still work for these people, but will they feel safe (in its broadest definition) using these channels in light of the current situation? Some will, some won’t.

That leads me to ask, what can the financial services industry do to help these people, who probably need this $1,000 the most, get the money into their accounts?

Overview by Peter Reville, Director, Primary Research Services at Mercator Advisory Group