The adoption of contactless payments in the U.S. has been underwhelming to say the least. Whether it’s via a contactless enabled card, a universal wallet (e.g., Apple Pay, Google Pay) or a store based wallet like Starbucks, only about one in five consumers have reported ever paying using these contactless methods for paying.

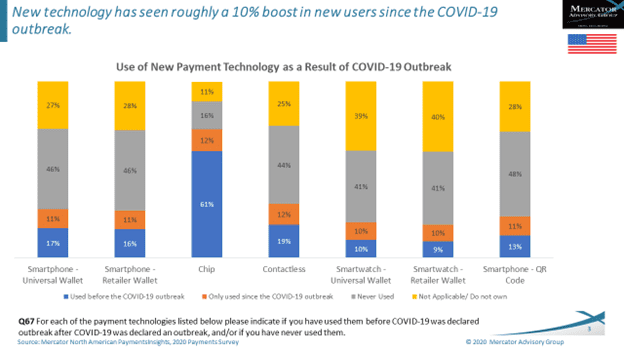

The graph below comes from our North American Payments Insights study which is a survey of 3,000 American adults. In this study, we asked people if they used contactless ways to pay before or since the pandemic arose. The reported use of contactless payments is pretty darn low for a technology that has been around for quite some time (in technology time), and that is much more widely used in other countries. Further, even with the widespread panic brought about by COVID and the fears of contact contamination only about 10% of new people used these payment modes.

An opinion piece in the NY Post, One-touch payments remain infuriatingly absent in America, puts the blame for lack of adoption squarely on the merchants inability or unwillingness to accept contactless payments with some shade being thrown on the merchant acquirers who provide the card readers at the point of sale.

Merchants, the most sympathetic party, are the culprits. Many smaller stores lease credit-card terminals from bigger networks, who have their own rules. Retailers who fear liability for fraud prefer to stay on the safe side — sticking to what they’ve done for decades.

The move to contactless is a complicated one. Particularly in the U.S. payment ecosystem which has a ridiculous number of players in the system. Placing the blame on one or two parties in this seemingly simple change to the way we pay is, quite frankly, a little naïve.

As I pointed out in a blog post this summer, there is enough “blame” (if you choose to call it that) can be spread out across all the stakeholders. At the risk of repeating myself I think the points I made at the end of July still apply:

How did we get to this point? Rather than assign blame, I think it is best to talk about how we overcome the obstacles.

Make “We Accept Contactless” Mean “We Accept Contactless”…Just Not Yours – There are competing standards and technologies currently required to accept the different versions of contactless. It is unreasonable to expect a merchant or consumer to know or care about this. When they see the contactless logo on a terminal, they should be able to use/accept contactless payments in all its forms.

Merchant education – Merchants, including frontline staff, need to know what contactless payments are and how they are accepted. Solve item 1 above and this will become materially simpler.

Consumer education – Just telling consumers that their card can now be used to “tap & go” or can be loaded into a wallet is not enough. They need to have a compelling reason to switch from tried and true payment methods before we can expect mass adoption. They also have to know they have a contactless card. Many people don’t know they have the capability available on their card. Solve item 1 above and this will become easier.

Broader issuance – Major issuers are phasing in contactless cards as expired and lost/stolen replacement cards are issued. This is going to take time. Even when we get to near universal issuance, item 3 above will be required.

On top of these suggestions to increase the use of contactless, the author of this piece make a very good point that I failed to make in July. There are still too many merchant acquirers who are asking for signatures and other POS interaction and data that are unnecessary and confound the seamlessness of a contactless transaction.

One merchant requires a phone number. Another wants e-mail. One machine wants you to pick credit or debit. Another insists you OK the amount. Still others want a signature. Then, another tap, for “OK.” There’s also the dreaded “chip malfunction.”

Not to mention that the major networks haven’t required signatures as an authentication solution some time ago.

Alas, something that is seemingly so simple is much more complicated that one have previously thought.

Overview by Peter Reville, Director, Primary Research Services at Mercator Advisory Group