Money mules, or individuals who transfer money acquired illegally, are a critical link in the fraud supply chain. As the threat of this type of fraud grows, it is becoming increasingly important for financial institutions to be able to detect it.

To learn more about the role of money mules in the fraud supply chain, PaymentsJournal sat down with Ayelet Biger-Levin, VP of Market Strategy at BioCatch, and Tim Sloane, VP of Payments Innovation at Mercator Advisory Group.

Register for the June 8th, 2021 Webinar!

Before Cash Disappears: Winning the Account Takeover Battle

Defining money mules and their role in the fraud supply chain

As previously mentioned, a money mule is a person who transfers money that was acquired illegally (i.e., stolen). This could be money from account takeover attacks or money laundering from human trafficking, drugs, or other illicit activities.

Mules transfer money from their accounts to the operator of the illegal scam. They may facilitate such transfers in person through a courier service or electronically on behalf of others. But what’s in it for them? “Typically, the mule is paid for their service, and they take a small percentage of the money that they transfer,” explained Biger-Levin.

Oftentimes, mules are recruited online for what they believe is legitimate employment. In these cases, they are unaware that the money they are transferring is the product of crime. Cybercriminals choose money mules through outlets such as frequently used social media accounts, online dating sites, online business websites, and online ads, contacting their targets and promising easy money.

The role of the money mule in the fraud supply chain

According to Biger-Levin, a simplified fraud chain has three main actors: those who create the tools to commit fraud (e.g., malware and virus tools), those who commit the crimes, and those who help with a cash out. Mules fall into the last category.

Mules and their accounts are a crucial component of the fraud supply chain. Simply put, cybercriminals would have nowhere to send their stolen money if it weren’t for mules. With nowhere to send the money, they would have no tangible way to steal it.

“At the end of the day, there is no account takeover fraud that can be completed without the use of money mules. And according to a survey by Aite Group, fraud executives that were polled in September 2020 cited that mule activity [was] the strongest growing segment of fraud attacks in 2020,” said Biger-Levin.

How FIs are tackling the growing mule problem

Today, financial institutions are looking at confirmed fraud cases and the velocity of transfers to accounts associated with fraudulent transactions. However, they face a major challenge in that mule accounts are not always within their financial institution.

According to Biger-Levin, the solution to this challenge lies in improved cross-collaboration between financial institutions. “Unless there’s an industry network to fight this type of fraud, there’s not much they can do about it. So that type of collaboration is really critical between financial institutions, and some such networks exist in the industry, but it’s not industry-wide. We need to augment that with different ways to be able to track mule account activity,” she said.

“These kinds of attacks are increasing at a huge rate and continue to climb during COVID. Figuring out how you can detect these different types of behaviors and personas is obviously critical, especially when you’re building models like BioCatch does,” explained Sloane.

The five mule personas FIs need to know

Financial institutions looking to solve the problem of money mules must first understand the types of money mules that exist because distinct types of money mules require different fraud controls.

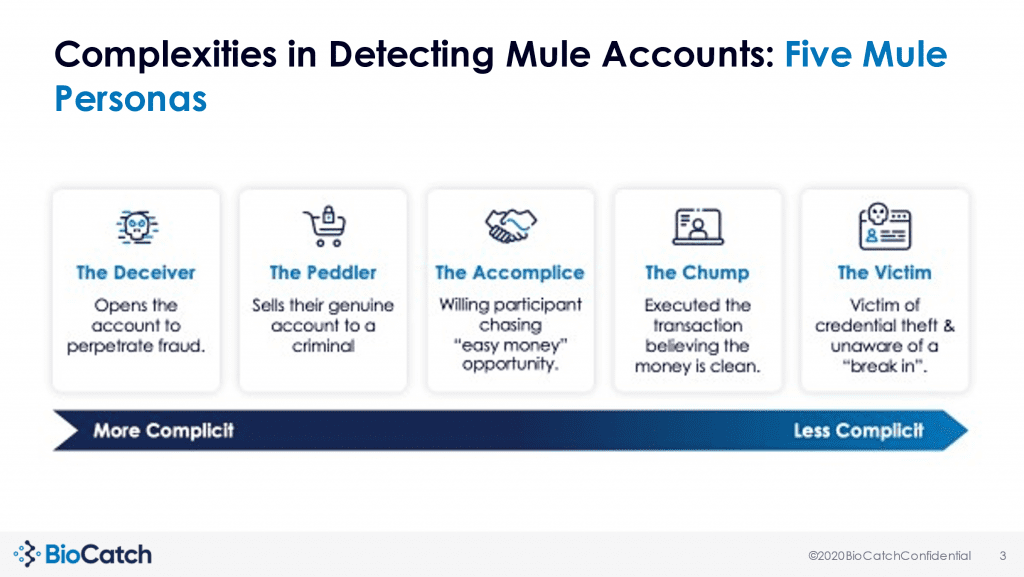

The BioCatch chart below depicts five distinct mule personas: the deceiver, the peddler, the accomplice, the chump, and the victim. They are organized from left to right on the chart by complicity, with the deceiver being the most complicit and the victim being the least complicit type of mule.

“What we do at BioCatch is we carefully look at a user’s digital, physical, and cognitive behavior to distinguish between cybercriminals and legitimate actors. We worked with our customers very closely to understand the mule problem and understand behaviors around mule accounts, and we realized that there are actually five personas that act as mule accounts,” said Biger-Levin.

Each of the five personas has distinct behaviors that can be identified, and once identified, FIs can put appropriate fraud controls in place. For example, deceivers are individuals who have obtained stolen personal information and use that information to open a fraudulent account for the purpose of cashing out money. If that mule is caught at the point of an account opening, FIs can stop deceivers in their tracks.

Meanwhile, peddlers (who sell their genuine account to a criminal) and victims (who are unaware that their account is being used for illicit activity) initially had legitimate accounts. For these mules, account opening fraud controls would not be effective, but changes in user behavior can alert FIs that an account takeover attack has occurred.

Accomplices and chumps are the most challenging personas to catch because they are legitimate users who open the account in a legitimate manner, but cybercrime is also occurring. “So how can we detect that someone is knowingly or unknowingly allowing money to be transferred through their account and cutting that percentage from the money? That is something we are able to do by looking at subtle behaviors that change over time, both on the user level and the account activity level,” Biger-Levin added.

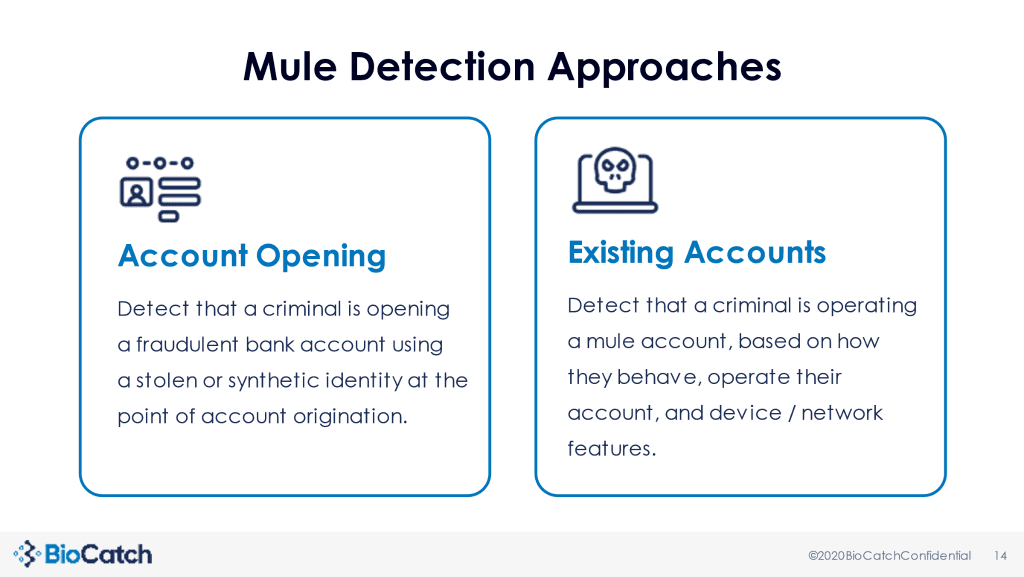

The chart below, provided by BioCatch, breaks down two mule detection approaches: account opening and existing accounts. The type of approach used depends on the type of mule FIs are attempting to stop.

Behavioral data and industry collaboration are crucial for success

BioCatch has been working with several global financial institutions to solve their mule problem. One of its first customers, a large FI in Australia, was able to identify over 2,000 mule accounts at a 1:1 genuine to fraud ratio in the first year thanks to the use of behavioral biometrics.

In the United States, banks have used behavioral biometrics to identify mule accounts that are being opened as part of the widespread stimulus payment fraud crisis that unfolded during COVID-19. This shows that, with the assistance of improved communication and collaboration in the financial services industry, mule accounts can be better identified.

“We, as an industry, need to get together to collaborate and to keep up with [mules] and get ahead of the curve,” concluded Biger-Levin.